| « earlier | later » |

The site will be down for maintenance this Saturday, March 22 from 19:00-21:00 California time (UTC/GMT -7). For people in Berlin, that's 04:00 Sunday. For Australians and kiwis, that's Sunday afternoon. The database is just about to run out of storage space, and unfortunately there's no way to free up room without shutting the beast down for a few minutes. I'll do my best to keep the downtime brief, and will post updates to Twitter as I go.

—maciej on March 19, 2014

Ladar Levison is raising money for legal defense after shutting down Lavabit, the encrypted email service he's been running for ten years.

Levison's problem is that he's barred from talking about what the government told him to do. But from circumstantial evidence, it appears he was being forced to installing monitoring equipment on his servers.

Levison has already taken a big risk by shutting the service down. Not only has he shuttered a project, but he risks prosecution for implicitly revealing the request for surveillance. And he's in the impossible position of trying to mount a legal defense without being allowed to talk about the case.

If you have been at all bothered by the scope of government surveillance on the Internet, please donate to Levison's fund. Even if you can only give a couple of dollars, it's important that we show up in large numbers, not just to support Lavabit, but to send a signal to the next small company that finds itself debating whether to fight a gag order, or publish a national security letter. They need to know we'll have their back.

Even if Lavabit fails in its appeal, the process will create a paper trail that may prove useful to future efforts at reform. We have to pick at every chink in the armor of secrecy.

If we don't support Lavabit, we'll send a signal of a different kind. A wealthy industry, one capable of throwing millions of dollars at the most nebulous of business ideas, will not put its money where its mouth is when it comes to defending the personal liberties it so vociferously advocates on message boards and in blog posts.

For my part, I'm pledging the next five days of Pinboard receipts to the Lavabit legal defense fund. If you've thought of joining Pinboard, or upgrading your account, you can do so now with the knowledge that all the money will go to Lavabit.

Please join me in donating whatever you can afford. Levison is currently $19,000 of the way to a $40,000 goal, but his costs will mount rapidly if the case makes it to higher appellate courts. If you're not comfortable with the rally.org site, there's a direct PayPal link you can use to donate.

—maciej on October 01, 2013

Last week I had the honor of presenting at XOXO, a wonderful conference organized up in Portland by Andy Baio and Andy McMillan. I've posted a text version of my talk here.

I had mixed feelings about speaking. The two Andys are wonderful people, and they had assembled a stellar list of attendees.

But that list made me a little uneasy. XOXO was an event full of establishment figures (myself included) preaching an alternative gospel. This led to some strangely dissonant moments, like an online billionaire exhorting us to build a better web, which he had presumably forgotten to do earlier. The audience was similarly packed with fossils from the the early Yahoo, antedeluvian Odeo, and pre-Cambrian blog eras.

There needs to be a web equivalent to the Salon des Refusés, where young punk kids with no money can come, make everything we've ever done look lame, and then roast us in our own food trucks.

XOXO has the right spirit for that, but the wrong butts in the seats. If it happens next year, maybe the selection rule can change to help the audience match the message.

I realize I risk sounding ungrateful saying so. But part of the strength of this conference, and why I hope it continues in future years, is the organizers' unusual willingness to listen, and their sincere committment to making the event wonderful. It can be thankless work organizing an event of this size, but I sure do hope they keep it going.

—maciej on September 27, 2013

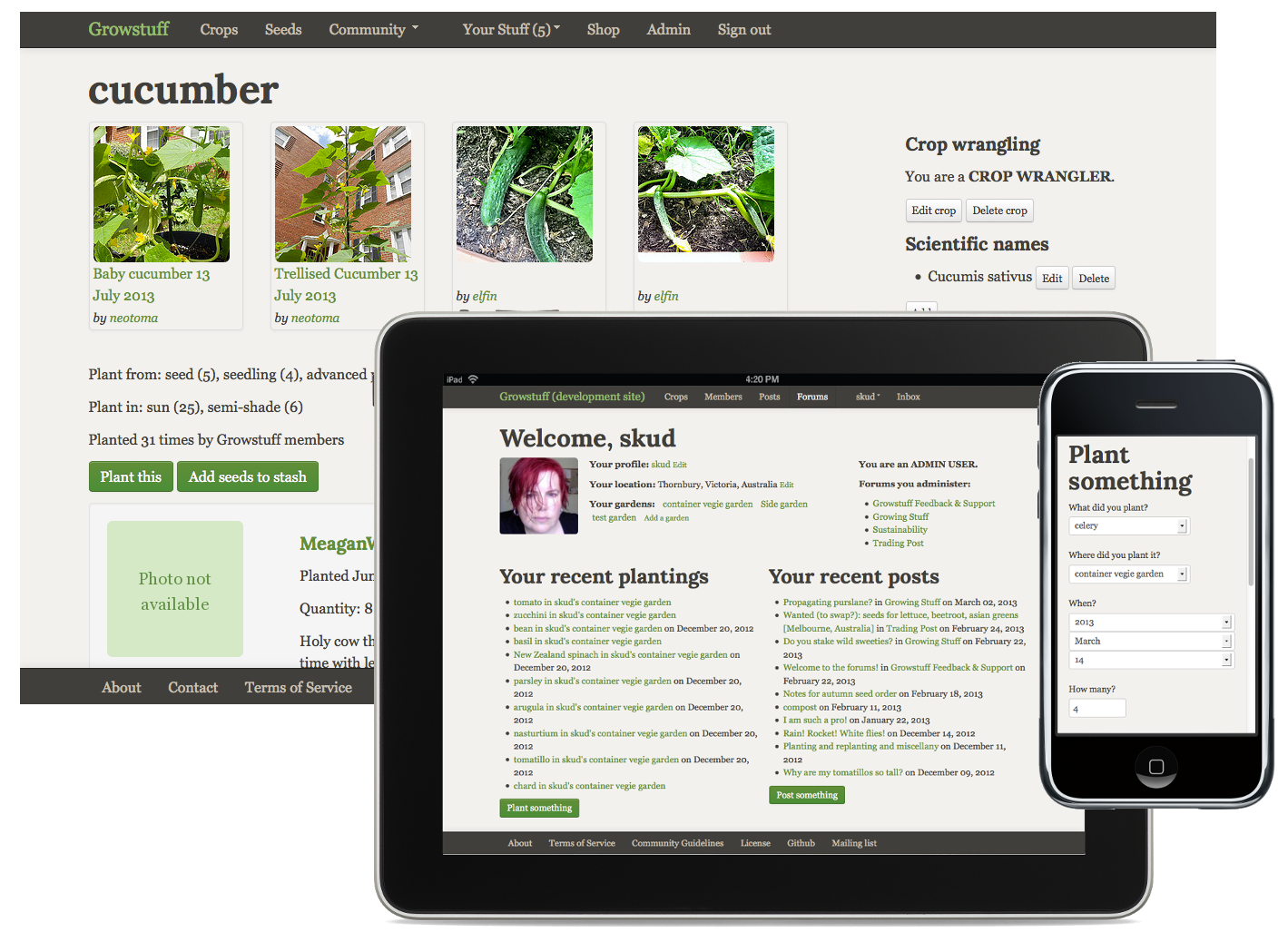

An Interview With Alex Bayley of Growstuff

Last year I chose Alex "Skud" Bayley as one of the six winners of the Pinboard Co-Prosperity Cloud, a prestigious $37 investment in six businesses that wanted to join me in thumbing their noses at Silicon Valley flapdoodle and just build something cool and mildly profitable on their own.

Alex's effort, Growstuff, is a community site for food gardeners. I think gardening is a terrific metaphor for maintaining a solo web project; there are dozens of small tasks that need frequent attention, or the site soon becomes unmanageable and withers. So I was curious to see what a community website around gardening would look like, and whether Skud could divert some of the energy from her industrious users to make her development efforts a little easier.

Skud had committed to open sourcing the site and making the development and planning process for it transparent, decisions that chilled me to the very marrow, but which she considered crucial to the success of her project. Reasoning that I had the most to learn from people who took a radically different approach, I forked over the $37 and sat back to see what would happen.

Several weeks ago, I got to meet Skud here in San Francisco, ate fancy little sandwiches with her, and got to hear a lot about her website. Now that Growstuff has launched, Skud has kindly agreed to share some of our conversation as an email interview:

MC: Congratulations on your public launch! What's next for the project in the months to come?

AB: Thank you! Our public launch was just the beginning. Our initial goal was to build something with basic functionality, that you could use to track your garden and which would also the potential of the site in terms of aggregating data and making it available both on the website and via an API. That's what we launched in June. It's only a small part of what we hope to build, though. We have heaps more to do, both in terms of user-facing functionality and in terms of our open data and API.

In July, I surveyed and interviewed a number of our members and we developed a roadmap for what's next. We had so many things on our development wishlist that we had to whittle them down somehow. In the end we came up with a list of things we want to work on that we think is achievable and that'll make the most people happy. It's posted on our wiki, but in short we want to improve the crop database; build ways to track your seed stash, harvests, and wishlist; work on a "1.0" API (as opposed to the current "version 0" we have); and a bunch of other little stuff.

MC: How did you spend my $37 investment?

AB: At that time, I was running Growstuff as a hobby project, and hadn't incorporated or anything. My only real expenses were web hosting, so it went to that. Which I guess is pretty much what you expected. Or another way of looking at it is that it paid for my groceries. When you have a hobby project and just one personal bank account, it's all a bit unclear. Since then I've incorporated Growstuff and the expenses have increased. I actually posted about our first few months' finances on the Growstuff blog. I found incredibly useful to see other small tech businesses' financial spreadsheets and breakdowns when I was just starting out, so I thought I'd pay it forward.

MC: How many garderners do you have going now? Is it following the usual pattern of a few very heavy users, and a larger number of occasional ones?

AB: Around 400 members at present. And yes, the usual activity distribution seems to apply, though the numbers are small at present and there is a pretty strong/active community of early adopters, so it's heavier on the "active" end than I'd expect to see when we have 400,000 members.

MC: You have a fairly extensive roadmap on the site, and it seems like you're amending it based on user feedback. What's the biggest divergence so far between stuff you planned and what has actually happened?

AB: Very little, really! We just passed our one year anniversary of the original idea of Growstuff, and I marked the occasion by revisiting the blog post I made back in July 2012. What I described there is basically what we've built (and are building). I think the vision of "Ravelry for food gardens" was pretty clear in the first place. It's only in the details that things have changed: we realised we needed to have a hierarchy of crops to note all the varieties of different things, we didn't manage to get international/alternative names for crops into the system as quickly as we would have liked, etc. But the overall bones of it are still what was originally talked about.

MC: When we spoke in San Francisco, it sounded like the open source part of the project had been a success, with a variety of people committing code. What's your secret to getting and keeping active contributors?

AB: Yup! We have over 100 people on our "discuss" mailing list where most of the dev work takes place. A lot of people join us because we advertise that we do pair programming and welcome non-experts. I suspect people stick around because it's a warm-fuzzy sort of project: you feel like you're doing something good and the people are friendly and appreciative. Plus a lot of people seem to just want something like Growstuff to exist, either for themselves or for people close to them. I hear a lot of people saying that their family members would be really into a site like Growstuff, and that seems to give them a really grounded sense of building something useful.

MC: Money! How do you make it, and is it enough to live on?

AS: Through paid memberships, which get you special features on the site (i.e. "freemium" model). At present these aren't enough to live on, but I'm also involved in an Australian government program for small businesses, which pays me about $1100 a month to work on this for 1 year. Between that and savings I'm doing okay for now, while Growstuff memberships are paying Growstuff's other expenses (including hiring a graphic designer, getting a lawyer to review our TOS, and stuff like that). I'll really need to start paying myself sometime in the next year, though, so we're going to have to build membership and make sure the paid accounts are compelling enough to get lots of people to subscribe and support the site and, ultimately, pay my rent.

MC: Is it true that Australia has a bizarre, non-cyclical pattern to its growing seasons, or is that just Yankee propaganda?

AB: Sort of true! There are at least four things that make Australian weather seem strange to northern-hemisphere people. The first, of course, is that the southern hemisphere is offset by 6 months due to the earth's axial tilt: our side of the world is closest to the sun around December-January. That sounds obvious, but wasn't so for the first white colonists here, who took a while to get used to it.

The second thing is that even in the temperate parts of Australia (including Melbourne, where I am) the seasons don't follow summer-autumn-winter-spring in quite the same way that eg. Europe does. For instance, summer for us is incredibly dry and hot, which means that it's *not* a peak growing time, unless you use a lot of artificial irrigation. Our lawns, for instance, tend to go through a growth spurt as the weather cools down. Here's a more realistic chart of seasonal trends in my area.

Then, thirdly, lots of Australia is in the tropics, which means that instead of having "summer" and "winter" it's just hot all the time and you have "wet" and "dry" seasons. And finally, Australia is very strongly affected by the El Niño/La Niña weather patterns, which have to do with slow-moving currents in the Pacific Ocean and involve multi-year fluctuations. So we often have a few dry years followed by a few wet years. When you hear about droughts and/or floods in Australia, it's often to do with this. So, all in all, it's complicated. And don't even get me started on our soil quality, which adds a whole new level of complexity for Australian gardeners trying to deal with growing traditions that were developed in Northern Europe. Ugh.

MC: Does the fact that gardening is a seasonal activity affect the rhythm of your work on the site?

AB: Not much, so far, though I expect that when our membership gets bigger we'll see distinct seasonality in our membership and activity. Northern hemisphere spring/summer is likely to be the busiest time.

MC: You've worked in the thick of things in the Bay Area, as well as back home. Would you advise people following your footsteps to get as far away from computerland as possible, or make an effort to be where other coders are?

AB: This is such a complicated question for me. I've had a very up-and-down experience in the tech industry, and the Bay Area had some of the highest "ups" and the lowest "downs". For me, being around heaps of incredibly smart people was great, but being around people intent on making bucketloads money at the expense of other peoples' wellbeing was horrible. I had mixed feelings about leaving, but I think it was the right choice. However, getting away from the Bay Area doesn't mean I got away from coders, and "computerland", if it's anywhere, is everywhere. I'm still working with coders every day, through in-person and remote pairing sessions and online discussions, but now I'm working with a different set of coders, mostly outside the Bay Area bubble.

As far as what I'd advise others: think hard about your values and act according to them. If your values match those of the Bay Area tech community, and you're able to do so, then by all means work there. If they don't, then don't.

MC: What can we do to encourage other people to start small, self-sustaining businesses?

AB: It seems like we have pretty strong informal networks to support each other, and I've had heaps of advice from you and from other indie tech founders. At the same time, I've found more formal groups (mailing lists, industry associations, meetups, etc) to be largely useless. I have no idea why this is, but I wish we could fix it.

I mentioned I've been involved in an Australian government program for small businesses. They weren't very tech-savvy, but as long as you ignored the tech side of things, they actually provided a lot of the information and training I needed when it comes to running a business: taxes, incorporation, planning, marketing, all that stuff. I'd love to see more of this.

Apart from that: I think we just have to keep doing what we're doing, and keep talking about why (and how) we're doing it. I think of indie tech businesses as being like farmers markets: there are lots of reasons to be unhappy with the systems of industrial food (or tech) production, but we can provide a meaningful alternative, and I think we have a growing community of people who appreciate that.

MC: Thank you so much for your time!

If you have a garden, big or small, aspire to have one, or just want to hack on some code in hopes of scoring some local vegetables, go check out Growstuff!

—maciej on August 26, 2013

An Interview With Alex Bayley of Growstuff

Congratulations on your public launch! What's next for the project in the months to come?

Thank you! Our public launch was just the beginning. Our initial goal was to build something with basic functionality, that you could use to track your garden and which would also the potential of the site in terms of aggregating data and making it available both on the website and via an API. That's what we launched in June. It's only a small part of what we hope to build, though. We have heaps more to do, both in terms of user-facing functionality and in terms of our open data and API. In July, I surveyed and interviewed a number of our members and we developed a roadmap for what's next. We had so many things on our development wishlist that we had to whittle them down somehow. In the end we came up with a list of things we want to work on that we think is achievable and that'll make the most people happy. It's posted on our wiki at http://wiki.growstuff.org/index.php/Roadmap_2013 but in short we want to improve the crop database; build ways to track your seed stash, harvests, and wishlist; work on a "1.0" API (as opposed to the current "version 0" we have); and a bunch of other little stuff.

How did you spend my $37 investment?

At that time, I was running Growstuff as a hobby project, and hadn't incorporated or anything. My only real expenses were web hosting, so it went to that. Which I guess is pretty much what you expected. Or another way of looking at it is that it paid for my groceries. When you have a hobby project and just one personal bank account, it's all a bit unclear. Since then I've incorporated Growstuff and the expenses have increased. I actually posted about our first few months' finances on the Growstuff blog (http://blog.growstuff.org/2013/07/05/show-me-the-money-growstuffs-finances-for-the-last-few-months/). I found incredibly useful to see other small tech businesses' financial spreadsheets and breakdowns when I was just starting out, so I thought I'd pay it forward.How many garderners do you have going now? Is it following the usual pattern of a few very heavy users, and a larger number of occasional ones?

Around 400 members at present. And yes, the usual activity distribution seems to apply, though the numbers are small at present and there is a pretty strong/active community of early adopters, so it's heavier on the "active" end than I'd expect to see when we have 400,000 members. You have a fairly extensive roadmap on the site, and it seems like you're amending it based on user feedback. What's the biggest divergence so far between stuff you planned and what has actually happened? Very little, really! We just passed our one year anniversary of the original idea of Growstuff, and I marked the occasion by revisiting the blog post I made back in July 2012: http://infotrope.net/2012/07/29/guadec-talk-done-and-a-new-project/ What I described there is basically what we've built (and are building). I think the vision of "Ravelry for food gardens" (http://ravelry.com) was pretty clear in the first place. It's only in the details that things have changed: we realised we needed to have a hierarchy of crops to note all the varieties of different things, we didn't manage to get international/alternative names for crops into the system as quickly as we would have liked, etc. But the overall bones of it are still what was originally talked about.When we spoke in San Francisco, it sounded like the open source part of the project had been a success, with a variety of people committing code. What's your secret to getting and keeping active contributors?

Yup! We have over 100 people on our "discuss" mailing list (http://lists.growstuff.org/listinfo/discuss) where most of the dev work takes place. A lot of people join us because we advertise that we do pair programming and welcome non-experts. I suspect people stick around because it's a warm-fuzzy sort of project: you feel like you're doing something good and the people are friendly and appreciative. Plus a lot of people seem to just want something like Growstuff to exist, either for themselves or for people close to them. I hear a lot of people saying that their family members would be really into a site like Growstuff, and that seems to give them a really grounded sense of building something useful.Money! How do you make it, and is it enough to live on?

Through paid memberships, which get you special features on the site (i.e. "freemium" model). At present these aren't enough to live on, but I'm also involved in an Australian government program for small businesses, which pays me about $1100 a month to work on this for 1 year. Between that and savings I'm doing okay for now, while Growstuff memberships are paying Growstuff's other expenses (including hiring a graphic designer, getting a lawyer to review our TOS, and stuff like that). I'll really need to start paying myself sometime in the next year, though, so we're going to have to build membership and make sure the paid accounts are compelling enough to get lots of people to subscribe and support the site and, ultimately, pay my rent. Is it true that Australia has a bizarre, non-cyclical pattern to its growing seasons, or is that just Yankee propaganda? Sort of true! There are at least four things that make Australian weather seem strange to northern-hemisphere people. The first, of course, is that the southern hemisphere is offset by 6 months due to the earth's axial tilt: our side of the world is closest to the sun around December-January. That sounds obvious, but wasn't so for the first white colonists here, who took a while to get used to it. The second thing is that even in the temperate parts of Australia (including Melbourne, where I am) the seasons don't follow summer-autumn-winter-spring in quite the same way that eg. Europe does. For instance, summer for us is incredibly dry and hot, which means that it's *not* a peak growing time, unless you use a lot of artificial irrigation. Our lawns, for instance, tend to go through a growth spurt as the weather cools down. Here's a more realistic chart of seasonal trends in my area: http://home.vicnet.net.au/~herring/seasons.htm Then, thirdly, lots of Australia is in the tropics, which means that instead of having "summer" and "winter" it's just hot all the time and you have "wet" and "dry" seasons. And finally, Australia is very strongly affected by the El Niño/La Niña weather patterns, which have to do with slow-moving currents in the Pacific Ocean and involve multi-year fluctuations. So we often have a few dry years followed by a few wet years. When you hear about droughts and/or floods in Australia, it's often to do with this. So, all in all, it's complicated. And don't even get me started on our soil quality, which adds a whole new level of complexity for Australian gardeners trying to deal with growing traditions that were developed in Northern Europe. Ugh.Does the fact that gardening is a seasonal activity affect the rhythm of your work on the site?

Not much, so far, though I expect that when our membership gets bigger we'll see distinct seasonality in our membership and activity. Northern hemisphere spring/summer is likely to be the busiest time. You've worked in the thick of things in the Bay Area, as well as back home. Would you advise people following your footsteps to get as far away from computerland as possible, or make an effort to be where other coders are? This is such a complicated question for me. I've had a very up-and-down experience in the tech industry, and the Bay Area had some of the highest "ups" and the lowest "downs". For me, being around heaps of incredibly smart people was great, but being around people intent on making bucketloads money at the expense of other peoples' wellbeing was horrible. I had mixed feelings about leaving, but I think it was the right choice. However, getting away from the Bay Area doesn't mean I got away from coders, and "computerland", if it's anywhere, is everywhere. I'm still working with coders every day, through in-person and remote pairing sessions and online discussions, but now I'm working with a different set of coders, mostly outside the Bay Area bubble. As far as what I'd advise others: think hard about your values and act according to them. If your values match those of the Bay Area tech community, and you're able to do so, then by all means work there. If they don't, then don't.What can we do to encourage other people to start small, self-sustaining businesses?

It seems like we have pretty strong informal networks to support each other, and I've had heaps of advice from you and from other indie tech founders. At the same time, I've found more formal groups (mailing lists, industry associations, meetups, etc) to be largely useless. I have no idea why this is, but I wish we could fix it. I mentioned I've been involved in an Australian government program for small businesses. They weren't very tech-savvy, but as long as you ignored the tech side of things, they actually provided a lot of the information and training I needed when it comes to running a business: taxes, incorporation, planning, marketing, all that stuff. I'd love to see more of this. Apart from that: I think we just have to keep doing what we're doing, and keep talking about why (and how) we're doing it. I think of indie tech businesses as being like farmers markets: there are lots of reasons to be unhappy with the systems of industrial food (or tech) production, but we can provide a meaningful alternative, and I think we have a growing community of people who appreciate that. A.—maciej on August 15, 2013

After a week of slogging servers around northern California, I thought a brain dump on colocation might be useful to readers, and to future me.

I wrote about the difference between colocation, leased servers and other kinds of hosting in an earlier post. This one is strictly about colocation, the 'Condo' approach where you own a bunch of hardware and need a place to put it.

What you are after is not complicated:

- A physical enclosure

- Some kind of Internet connection

- Power

- Security guards

Money

It's typical to sign a one- or three-year contract. Right off the bat this introduces an element of pressure, since you're making a fairly binding, long-term decision without knowing what you're doing. Unless you live in the Bay Area, colocation is a cost on par with your rent or mortgage.

Worse, I've found that the cost for identical configurations can vary by a factor of three or more. You really do need to shop around. And you need to be especially careful of punitive terms for things like overstepping bandwidth or power requirements. These are things you have to dig out of the fine print of contracts at a moment when you just want the whole process to be over.

Salespeople

Renting colo space feels like buying a car. You typically decide on a specific configuration you want, and then ask for quotes. For the salespeople involved, this is just the start of a long conversation they want to have with you. They'll be very curious about your budget, and want to talk about the hosting equivalent of an underbody clearcoat (various "hybrid cloud solutions") and extended warranty.

Although colo space is a commodity, salespeople become tetchy if you treat it as such. They will insist on talking to you over the phone and bristle at the suggestion that their job could be replaced by a web form. It is a good idea not to think about how much their salary or commission adds to your costs.

The reason I say colo space is a commodity is not because all facilities are the same, but because small-time clients will have no practical way of assessing their quality. There are certainly some facilities that are obviously bad, but most data centers have sane policies, look nice if you visit, and talk eloquently about uptime. The only way to evaluate a data center is to go through a series of small and big outages together, but by then you're already in a multi-year contract. So in practice, there is not enough information to pick a "better" data center, just a bunch of anecdotes on message boards. I believe you're better off getting space in two cheap places than trying to pick one high-end one.

Resellers

A lot of colo space is resold through intermediaries. This is often the only way to get a smaller amount of space than a full cabinet. Someone rents a bunch of cabinets at a data center and then parcels them out by the slice to clients, in pieces as small as 1u.

There are two things to watch out for in this arrangement:

- A bunch of people will have access to your physical equipment. Good resellers will take pains to introduce the various people in a cabinet to one another (or at least provide contact info).

- If your provider gets in a dispute with the data center, you may not be able to physically take out your hardware. It may even be seized without advance warning.

Power

Power is the great bugbear in hosting. You need to know how much your equipment uses, and how much you're likely to need. It is also often the limiting factor.

A useful rule of thumb in my case has been 1 rack unit = 1 amp. However, it is quite difficult to estimate the power consumption of a server before you buy it. You end up having to plug it in to a Kill-A-Watt meter under normal load.

A full cabinet is somewhere around 42 units, but a typical full cabinet power allotment is 20 amps. So you can't just fill a cabinet with servers.

The power situation is even worse than it sounds. That 20 amp figure is strictly theoretical, since you aren't allowed to use the full amount. You are limited to 80% of this figure, so a "20A" cabinet has 16A usable power, enough for eight pinboard-style servers.

Finding Datacenters

Finding information is another pain in the neck. The place of choice is an awful forum called WebHosting Talk. There is an open business opportunity to anyone who can stick a front-end interface on this site that lets you enter number of servers, bandwidth, physical location, and spit out a list of offers.

Another business opportunity is to make an authoritative directory of Bay Area data centers, since there is a bewildering assortment of sellers, re-sellers, and re-re-sellers offering the same physical space. Conversely, some large providers maintain multiple facilities.

Earthquakes

Nobody likes to talk about earthquakes. But anything in the Bay Area or Seattle is going to come crashing down at some point. Another thing that has proven impossible is finding out what facilities are at highest risk. It's one thing to go offline when the Big One comes (half the Internet will be down with you). But losing a rack full of hardware into the maw of the earth is worse.

So here's my plea to hackers: figure out where stuff is physically hosted, correlate it with seismic hazard maps, and make a nice web form that lets people shop for specific power/bandwidth/space configurations without talking to salespeople. Charge money for it! I will pay you! Others will pay you!

—maciej on August 03, 2013

| « earlier | later » |

Pinboard is a bookmarking site and personal archive with an emphasis on speed over socializing.

This is the Pinboard developer blog, where I announce features and share news.

How To Reach Help

Send bug reports to bugs@pinboard.in

Talk to me on Twitter

Post to the discussion group at pinboard-dev

Or find me on IRC: #pinboard at freenode.net